Richmond’s Monument Avenue: Introduction

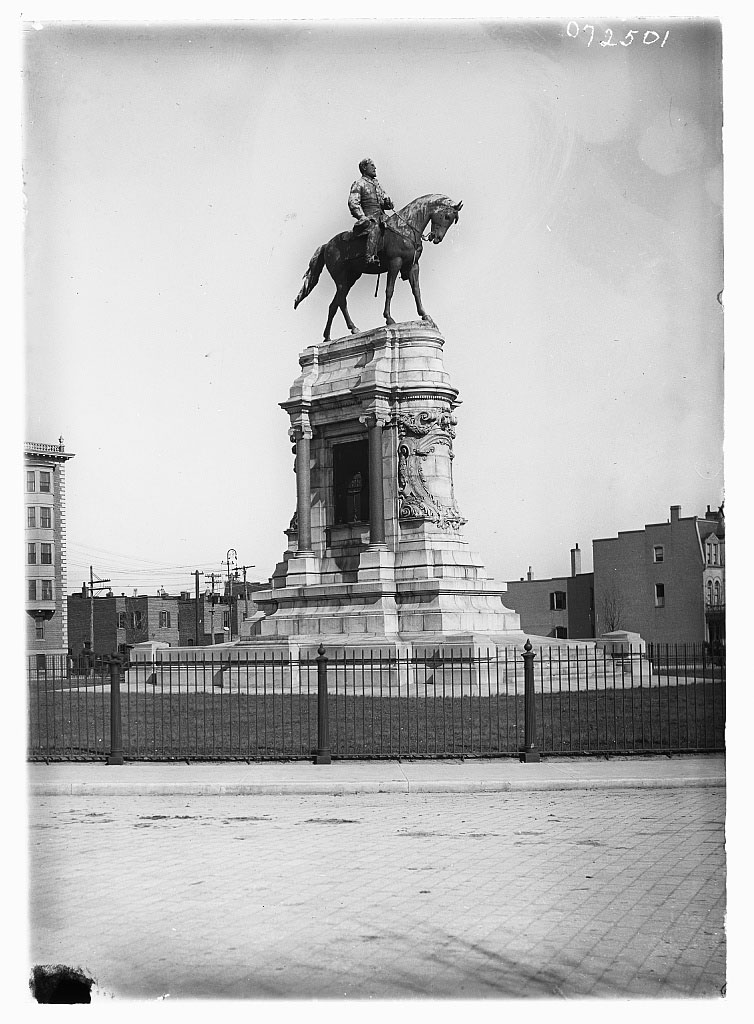

Richmond United States Virginia, None. [Between 1900 and 1915] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2016796908/.5 and 1920] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2016811716/

Many characterized the summer of 2020 in the United States as a racial reckoning, a moment where people in the U.S. learned about or articulated their sentiments about police and state violence against African Americans. As the summer progressed, more people began to protest the removal of Confederate and other racially problematic statues from their local, regional, state, and national landscapes. Many conservative members of the media and public criticized this as erasing history and the “Left’s triumph in the culture war.”[1] The most unsympathetic critics went so far as to argue that although some of these statues represented Confederate soldiers, colonizers, or enslavers, they were not hurting anyone by remaining up. Many activists and members of the public and state reacted in a variety of ways, from proposing legislation to remove the statues to forcefully toppling them off their pedestals. The Southern Poverty Law Center documented that out of the 826 Confederate monuments in the U.S., 66 were removed during or after the summer of 2020 compared to the three removed in 2015 and the 35 removed in 2017.[2]

One of the biggest sites of recent statue protests in the U.S. has been in Richmond, Virginia, particularly around the statue of Confederate general Robert E. Lee. This statue has been a public issue in the past, yet the summer of 2020 saw a new wave of protest that pushed the Governor of Virginia to propose legislation for Lee’s removal. On October 27, 2020, the circuit court ruled that Governor Northam can remove the statue but halted immediate action, allowing time for groups opposed to removal to state an appeal.[3] Activists removed other Confederate statues in Richmond by force, including Confederate President Jefferson Davis’ statue that was nearby Lee’s. Richmond Mayor Levar Stoney ordered the other nearby Confederate statues honoring Stonewall Jackson, J.E.B. Stuart and Matthew Fontaine Maury to be removed the summer of 2020, stating the protests around them were a threat to public safety.[4]

Together, these five statues comprised Richmond’s notorious “Monument Avenue,” a boulevard that housed the elite business class in early twentieth century Richmond and created a desirable neighborhood. The Monument Avenue area continues to be prized as a beautiful, historically preserved district in Richmond. Judge Bradley B. Cavedo, who was assigned to the Lee case and ruled initial injunctions over the summer of 2020, is a resident of the area. His residency in the Monument Avenue historic district was actually the reason he later recused himself from the Lee case. How does Cavedo’s residency play into his seeming bias towards the Confederate statues? What does Cavedo’s recusal say about the relationships between Monument Avenue residents and the statues? Moreover, what does this decision – and the history of the surrounding neighborhood at large – say about the general relationship between statues and the spaces they live in?

This paper will address these questions, particularly around statues’ effects on the spaces they inhabit and the communities around them, by viewing the specific case study of Monument Avenue in relation to both the surrounding neighborhood and the greater city of Richmond following Reconstruction. Using Lee’s statue as an anchor to Monument Avenue itself and the surrounding Monument Avenue neighborhood, I argue that statues can give financial and cultural value to different spaces, reinforcing certain ideas and hopes people have of themselves and the region they represent. In the case of Richmond, the Confederate statues helped build not only Monument Avenue and its surrounding neighborhood but also a legacy of centering cultural value and economic progress while de-centering racial issues present in a post-Reconstruction world.

[1] Selwyn Duke, “Toppled Statues to Toppled Republic?” The Last Word, The New American July 20, 2020.

[2] “Whose Heritage? Public Symbols of the Confederacy” Southern Poverty Law Center February 1, 2019. https://www.splcenter.org/20190201/whose-heritage-public-symbols-confederacy#executive-summary.

[3] Laura Vozzella “Northam can remove Lee statue in Richmond, judge rules” The Washington Post, October 27, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/virginia-politics/richmond-judge-lee-statue-removal/2020/10/27/6fe87166-1893-11eb-82db-60b15c874105_story.html.

[4] Stoney said that the statues would be put in storage until a public decision is reached about what to do with them in the long-term. Laurel Wamsley, “Richmond, Va., Mayor Orders Emergency Removal Of Confederate Statues.” NPR. July 1, 2020. https://www.npr.org/sections/live-updates-protests-for-racial-justice/2020/07/01/886204604/richmond-va-mayor-orders-emergency-removal-of-confederate-statues.