by: Janine Hubai

U.S. Army bases named after Confederate soldiers are a controversial topic and one that was protested in the Summer of 2020. The controversy lies deep in public memory of the Civil War. Those who support the name change give three reasons for renaming: the support of slavery of Confederacy and Confederate soldiers, the fact that many U.S. military officers who resigned from the U.S. Army to join the Confederate Army committed treason against the United States, and that the use of Confederate names lack respect for People of Color who serve in the armed forces and the names can result in racial intimidation. Those against changing the bases names often say Confederate officers should be celebrated for defending state’s rights and for their military heroics as reasons to keep the names.

For many years, the Army said that naming bases for Confederate soldiers was an act of reconciliation between the North and the South, and not a political act. However, on July 9, 2020, Joint Chiefs of Staff General Mark Milley said the Army needed to address how Confederate base names affect Black soldiers. He said, “For those young soldiers that go onto a base- a Fort Hood, a Fort Bragg or a fort wherever named after a Confederate general- they can be reminded that that general fought for the institution of slavery that may have enslaved one of their ancestors.” He went on to say that political decisions were made when naming the bases during World War I and World War II, and the debate on whether they should be renamed today are going to be political decisions. The protests of 2020 thrust Confederate base names into the national debate of racial reckoning.

This exhibit views public issues of race through a military lens to show that naming Army bases was political in both World Wars and that contestation over Confederate base names is not a new phenomenon. It considers the politics of naming Army bases in World War I and World War II and its connection to current issues of racial reckoning. The exhibit has three parts: 1) How Army bases received their Confederate names during WWI and WWII; 2) Highlights Black voices in the process of naming bases by looking at the ways Army installation commanders advocated for naming Army camps and sports fields for exceptional Black soldiers and protests by Black Americans against Confederate symbols during WWI and WWII; and 3) Ways the Army is working towards removing Confederate base names and why this is significant.

First, understanding the concepts of the Lost Cause narrative and Sectional Reconciliation are important to understand the history behind the base naming.

Sectional Reconciliation and the Lost Cause

. [, monographic. Clif Edson Music Publisher,, Brockton, Mass.:, 1918] Notated Music. https://www.loc.gov/item/2013562194/.

After the Civil War, the South entered a period of Reconstruction, when the U.S. Federal government sought to rebuild the Southern economy after the Civil War and the end of slavery, and create an environment that gave more rights to Black Americans, many recently enslaved. This continued for about a decade before the North and the South entered a period of Sectional Reconciliation. As David Blight argues in his book Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory, sectional reconciliation brought White Northerners and White Southerners under a national narrative that enough time had passed that old Civil War wounds could be healed and the nation could recognize its shared military experience in the war as one that was equally honorable.

While soldiers took part in this reconciliation, civilians also sought this unification of both sides. Blight says a move towards sectional reconciliation came at the expensive of Black Americans. Reconstruction was a complicated process that required a long term commitment to bring racial equality in the South and rebuild the Southern economy after the war. White Northerners grew tired and disinterest in supporting Reconstruction efforts. Soon after the war, the South quickly embraced The Lost Cause narrative which viewed the Civil War as a war fought over state’s rights versus federal rights and ignores the idea that the Confederacy fought over the right to continue the institution of slavery. Ultimately reconciliationists (those hoping for the North and the South to make amends) conceded to the Lost Cause myth pushed by white supremacists to forge union and forgiveness, pushing aside the freeman’s cause in emancipation and reconstruction. As history tells us, Jim Crow laws soon emerged in the South allowing legal segregation which further reduced rights of Black Americans.

America’s participation in the Spanish-American War strengthened the reconciliation as many viewed the war as the first conflict that gave all Americans- whether from the North or South, or regardless of race- a united reason to fight a war. As children of Confederate and Union soldiers fought together, the division between the two regions lessened, yet racists policy and violence increased against Black Americans.

Two World Wars: Building Military Installations

When America made the choice to fight in World War I, the Army needed to quickly build training camps around the country to train the 4 million men who served in the military during the war. During World War II, additional camps were built to train the 8 million men and women who served. These camps needed names! Most of the current U.S. Army bases were named during the training and preparation for World War I and World War II. As the documents below show, much consideration was taken into account when choosing names, especially when it came to White soldiers.

Millions of Americans signed up to fight in the wars, including many Black Americans who hoped to continue their long legacy of military participation. While they were accepted into the Army, the Army conceded to Southern pressure to segregate the Army. Black soldiers served in segregated units led by Southern White officers. They had separate training drills and living quarters and could not use certain facilities at the camps, even if they served in Northern military camps where the local communities did not practice Jim Crow segregation. Black soldiers mainly served in the quartermasters as most were banned from combat units. Like many Confederate named public statues and entities, Confederate named military bases fueled negative and harmful feelings in People of Color.

World War I: Base Naming

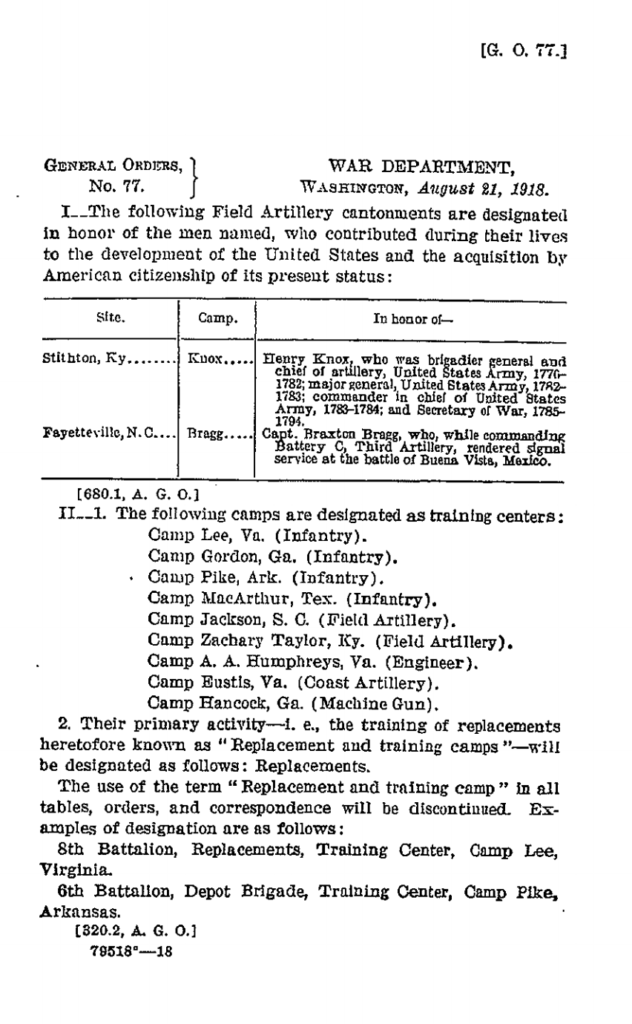

In naming these camps, the Army look towards names that would create pride and national spirit within the local community and among the soldiers as it improved soldier morale and garnered support for the war in the local communities. In 1917, Brig. Gen Joseph E. Kuhn set eight criteria which should be met in naming army camps which included “(1) represent a person from the locale of the troops stationed there, (2) that it be “not unpopular in the vicinity of the camp,” and (3) that it focus on “Federal commanders for camps of divisions from northern States and of Confederates for camps of divisions from southern States.”[1] A number of names were accepted and rejected throughout this process, but overall only four of nineteen camps in the South were named after Confederate officers: Camp Lee, Camp Beauregard, Camp Gordon, and Camp Wheeler. Others were either named for Northern officers or Southerners who fought in wars prior to the Civil War, as well as two U.S. Presidents who enslaved Black people, Andrew Jackson and Zachary Taylor.

The politicians and the military needed to court Confederate sympathies- both for enlistment rates and general public support. No regard was given to Black soldiers, despite over 350,000 men who served in the Army during WWI. Black soldiers were assigned to numerous bases throughout the United States, and many were forced to serve on segregated bases named for Confederate soldiers or other enslaver American leaders.

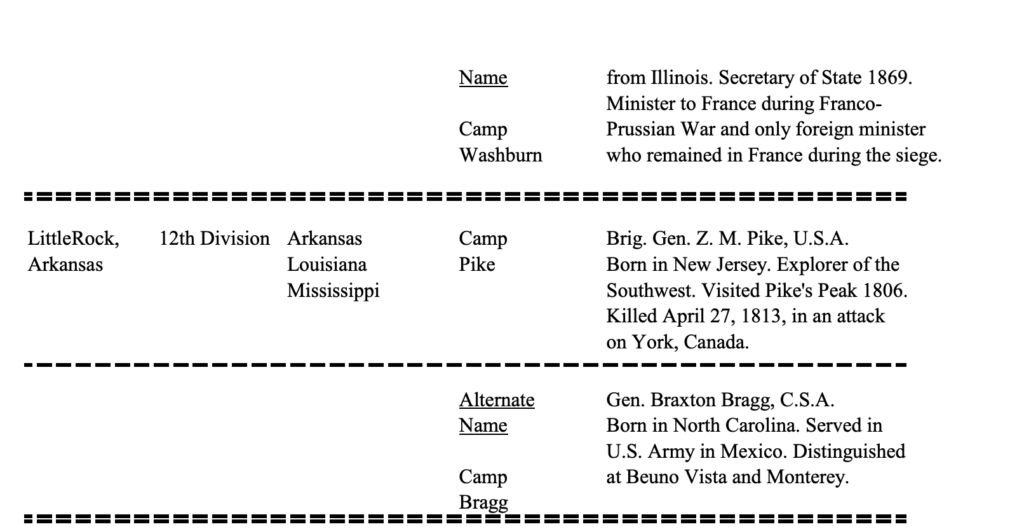

Fort Bragg in North Carolina was named during World War I. Braxton Bragg, a U.S. Army officer before the Civil War and a General in the Confederate States Army (CSA), was considered for a camp name during World War I. A 1917 War Department memo about suggested camp names lists Gen. Braxton Bragg, his rank in the CSA listed, as an alternative name to Camp Pike in Arkansas. While his name was not chosen for the camp’s name in Arkansas, his name was chosen for the camp name in North Carolina. The official orders dated in 1918 listed Bragg’s rank as captain which was his rank in the U.S. Army, and not his higher rank of General with the CSA. At this time, it is not known why the Army chose to list his service this way on the official orders, but future research might reveal whether the reason was to reconcile a conflict, hamper Confederate connections, or some other unknown reason. Fort Bragg has flourished to become one of the largest military installations in the world, training numerous Black soldiers since WWI. While the local community could not stop the training of Black soldiers in the Army, segregation persisted on the base throughout both world wars and the significance of the name was not lost on Black soldiers who recognized Bragg as an enslaver.

World War II: Base Naming

The massive growth of the military during World War II required the construction of even more military infrastructure. During WWII, the same segregation practices existed for Black Americans as they did during WWI, although more were able to fight in segregated combat units. Over one million Black men and women served in the Army during WWII. While they served in a wider array of roles than the first World War, many continued to serve in quartermaster units or were assigned menial tasks in other units.

During World War II, eight major camps were named after Confederate soldiers: Camp Polk, A.P. Hill Military Reservation, Camp Gordon, Camp Pickett, Camp Rucker, Camp Hood, Camp Forrest, and Camp Van Dorn. The Army continued to carefully name the camps and bases.

The army continued to weigh Southern Confederate sentiments. A memorandum issued by The Secretary of the Historical Section of the Army War College on September 17, 1940 includes notes associated with Southern sensitivities surrounding Civil War names in the South. The note reads, “Civil War names, because of local sentiment, can only be used with caution; moreover, one Army camp in Louisiana already commemorates a Confederate soldier.”[2] The Army concerns about Confederate local sentiment could have been for a number of reasons. Strong loyalties to an idea such as the Lost Cause narrative that weakened federal influence could hamper support for the war. Again, politicians and the military needed to balance the local sentiments with federal needs. But also, Black soldiers and civilians were much more vocal and active about their civil rights in the military. Confrontations between White and Black soldiers were violent in the 1940s. The Army did not want more fuel for that fire.

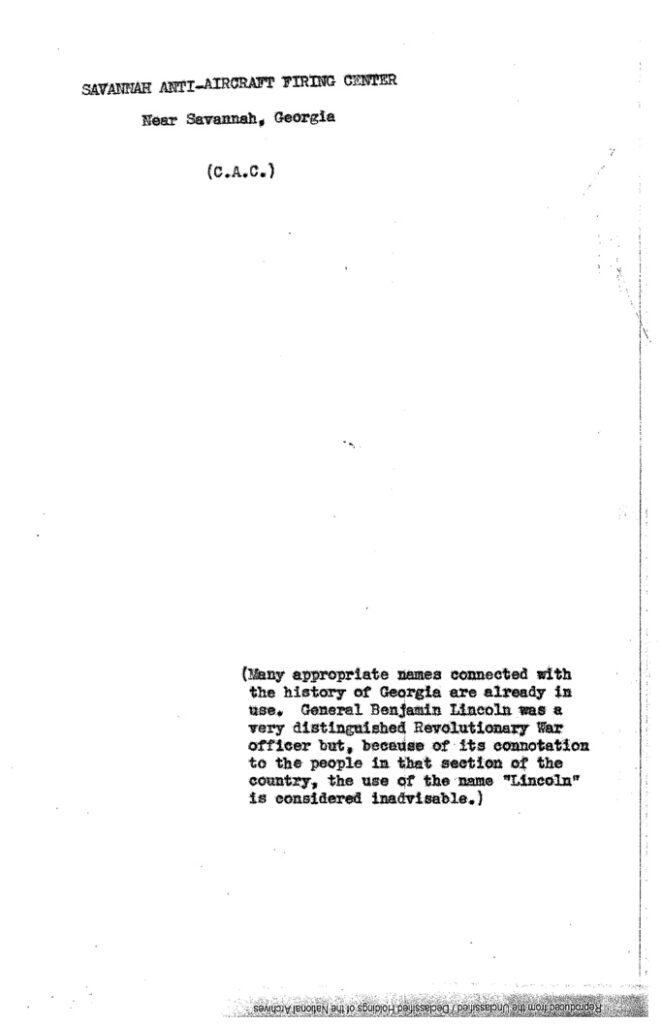

Another Army document from 1940 further shows the South’s Lost Cause sentiments during the World War II era, including Southern feelings about Abraham Lincoln. When discussing naming for the Savannah Anti-Aircraft Firing Center, a War Department memo suggested a Revolutionary War Officer Gen. Benjamin Lincoln but advised against the name as the “connotation” of the name Lincoln “to the people in that section of the country.”[3] Even though the Civil War ended almost 80 years prior, people in the South continued to resent leaders of the Union. The base was named Camp Stewart after a Revolutionary War hero, instead of using the name Lincoln. Here we see the Army conceding to the Southern notions of the Lost Cause narrative, and certainly choosing to placate White Southern sentiments to minimize names that would be considered divisive, a narrative the Army also used in 2017 to as a reason against renaming bases with Confederate names

These sets of World War II memos tended to connect soldiers to their CSA military service: General Order issued June 11, 1941 named A.P. Hill Reservation in Caroline County, Virginia as a Major General in the CSA, as subsequent orders also connect CSA service in name designations.[4].

While the military was looking for support of the wars from the general public and enlistment, the conversation shows that the military was more concerned about White citizens and soldiers and not the Black citizens and soldiers in the regions. Politics certainly played a large role in these base names, but these examples highlight the continued concessions to White, dominate Americans despite calls for recognition of Black military service and protest by Black Americans.

World War II: Black Soldiers and Army Base Names

Military service was important to Black soldiers as they saw military participation as a means to equal citizenship in American society. If Black men were good enough to fight in American wars, then they deserved the same citizenship rights as white Americans. This was an era when soldiering defined masculinity and valor. There are examples of commanders of Army installations advocating for names of Black soldiers and Black civilians protesting Confederate base names. Here I present two examples of military structures given names of Black soldiers and one such base that was protested against.

The Army’s desire to name installations that would build spirit within units is evident in the naming for an embarkment center for Black soldiers in Seattle, Washington. Five Black soldiers with exceptional valor and military service were recommended to be used as a name for the base. The Adjunct General in Washington, D.C. responded by directing the camp to be named Camp George Washington Carver on August 10, 1943.[5] While Carver’s accomplishments as a scientist and proponent for equality for Black Americans is heroic, the name denies Black soldiers to serve on a base named after a Black soldier that exemplifies valor and masculinity through military service.

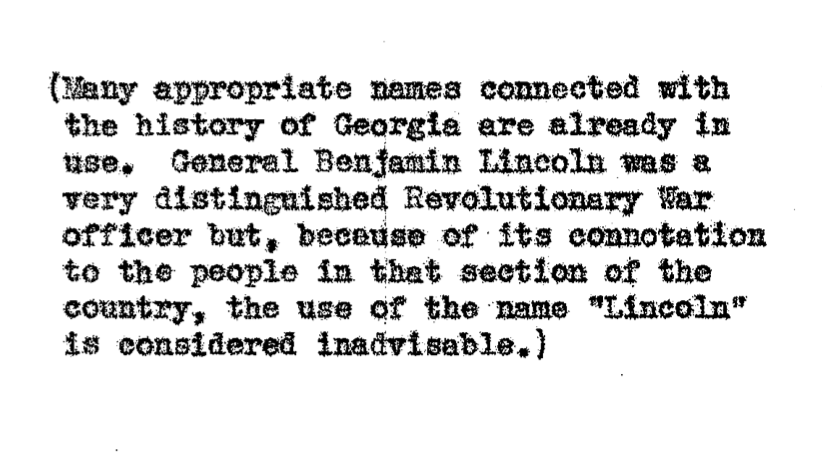

While the Army documents do not show the discussion about why the Army did not name the camp after Carver, an order issued in October 1943 by Brigadier General Eley P. Denson recommended the embarkment port be named Camp George Jordan after Sergeant George Jordan, thirty year veteran of the U.S. Army who distinguished himself with the 9th Cavalry K Troop by earning a Medal of Honor Recipient as a Buffalo Soldier.[6] The order is approved for the name change. In this example, the Army had the opportunity and support from some of its members to name the base after someone who reflected the Black soldiers who served there. While the Army supported the name in this case, other cases were not as successful.

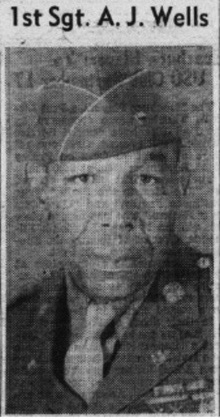

At Fort Huachuca in Arizona, several buildings and structures were named for Black Americans associated with the base. The base housed the largest training facility for Black soldiers during WWII. Commanding officer Edwin N. Hardy asked for permission to circumvent naming rules that stated the namesake must not be living, to recommend that a new football field be named after Brigadier General Benjamin Davis, the only Black General in the Army at that time. Hardy said naming structures for prominent Black Americans connected with the base “undoubtedly creates pride and morale in the troops serving at this station.” Hardy’s request was denied, but the football field was named after First Sergeant Andrew J. Wells, a Black man who had a 25 year Army career and was well respected.

These incidents show that some military officers did have concerns about Black soldiers’ morale and advocated for appropriate naming. Yet these examples are outside of the Southern region and on predominantly Black training facilities.

Concurrently there was a movement by Black citizens against segregation and civil rights injustices in the Army and Confederate base names in this period. Camp Forrest in Tennessee, named after enslaver, Confederate Officer, and founder of the Ku Klux Klan Nathan Bedford Forrest, came under protest by the Black newspaper The Chicago Defender in its February 1, 1941 issue. Roscoe Conkling Simmons of The Defender calls out the War Department for using Bedford’s name relaying the story of the Fort Pillow Massacre during the Civil War. Forrest attacked the fort and his men killed over 200 Black soldiers who had surrendered. “Remember Fort Pillow” became a rally cry for Black soldiers. Simmons points out that even General Lee and Jefferson Davis denounced the massacre. As Black soldiers from Illinois were stationed at Camp Forrest, Simmons said, “Now soldiers of Illinois, state of Lincoln, Grant, and Logan will get their mail, ‘Camp, Forrest, Tenn.’ Forrest shouted to his men, ‘Kill every [n-word] and every white man fighting with them and for them.’ The Forrest crowd is still in full cry.” This example shows a long history by the Black community against Confederate base names and an American society that was presented with these objections for over 80 years.

Mark Milley acknowledged that in his early career years at Fort Bragg, long after integration of the armed forces in 1948 and a decade after the 1960s civil rights movement, a Black Staff Sergeant told Milley that he went to work every day on a base that represented a person who enslaved one of his ancestors.

Confederate Army Base Names in 2020-2021

Many military leaders are acknowledging the need to change the name of Confederate bases. Retired General David Petraeus wrote an article in The Atlantic on June 9, 2020, relating his own personal journey in realizing the significance of these base names and why they should be changed. Petraeus, moving away from a rhetoric of reconciliation or arguments that it is either too divisive or difficult said, “The United States is now wrestling with repeated instances of abusive policing caught on camera, the legacies of systemic racism, the challenges of protecting freedoms enshrined in the Constitution and Bill of Rights while thwarting criminals who seek to exploit lawful protests, and debates over symbols glorifying those who fought for the Confederacy in the Civil War. The way we resolve these issues will define our national identity for this century and beyond.”[8] He understands the significance of this moment, and the power to change the narrative in the United States, knowing that America has been here before.

Many military leaders, including Joint-Chiefs-of-Staff Chairman General Mattis and Former Defense Secretary Mark Esper support the renaming of Confederate bases. The House of Representatives and the Senate drafted a bill requiring the renaming of Confederate bases within the next three years. This is important as many participants in the event at the U.S. Capitol on January 6 are active military or veterans. This event included people wearing and carrying many symbols of hate groups. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin, first Black person to hold this position, issued a “military wide ‘stand-down’ to address extremism in the ranks” as “nearly 1 in 5 people charged in connection with the riot have some form of military background.”[9] The military has a right to be concerned about racists symbols in the military.

Petraeus says the names should be removed to follow that second criteria of Army Regulation 1-33 that says memorializing deceased soldiers and individuals should benefit all races in society and inspire soldiers, employees, and other races. Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Mark Milley did say that Confederate Flags, another Confederate symbol used by some military members, could affect unit cohesion and effectiveness as over 40% of the Army are People of Color.

Politics played a large part in how bases obtained their names, despite the decades-long denial by the U.S. government and Army who pushed forward the notion of reconciliation. Decisions were made based on Southern sentiments in regards to The Lost Cause, and these decisions ignored the Black men and women serving in the military. These base names add to the list of ways the military denied or hindered service for Black Americans. More research is needed to understand the decision-making by politicians and military officials of the rules underlying base names and the ultimate decision themselves. Not only with this help to bring more inclusion in the armed forces, but also help us to understand the deep structural racism in America’s foundations, as America reckons with its racist tendencies.

Afterall, the military is a reflection of our society.

Update: Since the writing of this post, the Army removed Confederate names from bases. You can read an update here and here.

[1] “Naming of Army Posts,” U.S. Army Center of Military History, https://history.army.mil/faq/naming-of-us-army-posts.htm, accessed November 29, 2020.

[2] “Memorandum for the Secretary, Historical Section, A.W.C.” Historical Section, Army War College, September 17, 1940. U.S. Army Center of Military History. https://history.army.mil/faq/army-posts-documents/075-Post_name_suggestions_Sep_1940.pdf.

[3] Ibid.

[4] General Orders No. 5, War Department, June 11, 1941. U.S. Army Center for Military History. https://history.army.mil/faq/army-posts-documents/100-GO_5_(11_Jun_1941).pdf

[5] “Memorandum for Operations Branch, A.G.O, Class IV Camp Under Seattle Port Embarkation,” August 20, 1943, Col. John W. Wright. U.S. Army Center for Military History, https://history.army.mil/faq/army-posts-documents/140-Corresp_re_facilities_named_for_African_Americans_1942-1943.pdf.

[6] Letter, Brigadier General Eley Denson, October 2, 1943, U.S. Army Center for Military History, https://history.army.mil/faq/army-posts-documents/140-Corresp_re_facilities_named_for_African_Americans_1942-1943.pdf; “George Jordan A Soldier’s Soldier,” National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/people/george-jordan.htm.

[7] https://history.army.mil/faq/army-posts-documents/155-Camp_Adair_1942.pdf

[8] David Petraeus. “Take the Confederate Names Off Our Army Bases It is time to remove names of traitors like Benning and Bragg from our country’s most important military installations.” The Atlantic, June 9, 2020. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/06/take-confederate-names-off-our-army-bases/612832/.

[9] Ellen Mitchell, “Pentagon Chief Orders Military wide ‘Stand-down’ to Tackle Elusive Issue of Extremism,” The Hill (The Hill, February 4, 2021), https://thehill.com/policy/defense/537251-pentagon-chief-orders-military-wide-stand-down-to-tackle-elusive-issue-of?utm_source=thehill&utm_medium=widgets&utm_campaign=es_recommended_content.

[10] Meghann Myers. “Military’s top officer is open to renaming Army posts honoring Confederate generals.” July 9, 2020, Military Timeshttps://www.militarytimes.com/news/your-military/2020/07/09/militarys-top-officer-is-open-to-renaming-army-posts-honoring-confederate-generals/.