Richmond’s Robert E. Lee Statue

The fundraising, sculpting, and placement of Robert E. Lee’s statue in Richmond was a cultural reunion with the Confederacy and an economic plan for the city. Upon Lee’s death in 1870, ex-Confederate President Jefferson Davis headed the Lee Monument Association. There were different groups involved in the matter, including the Ladies’ Association and soo the planning did not move forward substantially until the 1880s when the Governor, Treasurer, and Auditor of Virginia comprised the Lee Monument Association’s board. By the late 1880s, the Governor of Virginia was Fitzhugh Lee, Robert E. Lee’s nephew, who spearheaded the monument planning and particularly the location of the monument. In 1886, Governor Lee laid out a “plain business proposition” to Richmond’s board of alderman that the monument, if placed in an undeveloped lot west of the city’s center, would create a desirable new subdivision. Specifically, Lee argued that if the city appropriated money for the monument’s pedestal or base, over time the city would gain an “excess of income” via property taxes.[1] Lee also emphasized that “If the city limits were extended to embrace an equal area west of the monument site the financial results would, of course, be still better,” suggesting developments west of the monument would be profitable. [2] City leaders bought into Governor Lee’s business proposal and the Lee statue was unveiled in 1890 in the proposed location, strategically placed for the future Monument Avenue and the surrounding all-white elite residential area. Pierre Nora claims that people use the past to say something about themselves in the present.[3] Kirk Savage points out that the past can also be used to say something about the future; the Lee statue was placed “into the city of the future – a residential neighborhood not yet even built.”[4] The proposed location of Lee’s statue indeed says a number of things about Governor Lee, real estate developers, and Richmond city leaders: they hoped to use a monument to create a white subdivision that would give them profit over time.

Though Governor Lee’s proposal to the board stated that he “made no appeal to Confederate feeling,” many other people – especially white Southerners – interpreted the Lee statue and the subsequent statues as symbolic gestures celebrating the Confederacy.[5] The United Daughters of the Confederacy organized huge gatherings for statue unveilings, including Monument Avenue’s Jefferson Davis statue, which illustrate white Southerners explicitly connecting the dedication of a Confederate soldier to the celebration of the Confederacy. Festivities around dedication ceremonies were ritual gatherings of the entire white community, including children, where people sang “Dixie” and waved Confederate flags.[6] Statues were also sites for Confederate veteran reunions, particularly with the Lee statue in Richmond. Records shows that before other statues were added nearby and before Monument Avenue was fully built out as a neighborhood, veterans reunions took place by the Lee statue.[7] Clearly, veterans saw the Lee statue more as the site of the reunion and less of a future subdivision. These examples show that white Southerners not only perceived but engaged in actions that demonstrate Lee’s monument and the subsequent others had cultural symbolism celebratory of the Confederacy and were not mere economic projects to them.

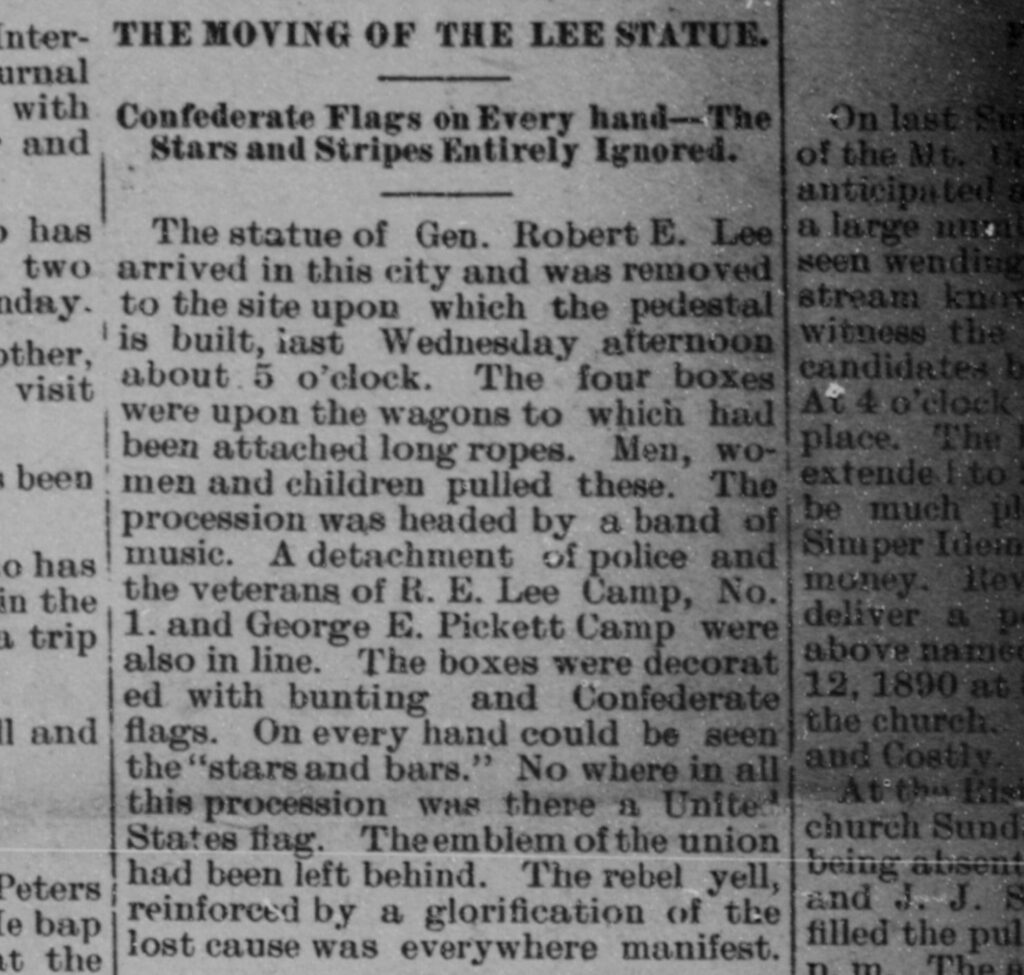

African Americans interpreted the Lee statue, and Monument Avenue by association, as an explicit celebration of the Confederacy and by extension white supremacy. Black protest of Confederate statues was always a part of the discourse in Richmond, beginning with criticisms of the Lee statue. John Mitchell Jr., the editor of the Black newspaper Richmond Planet, published explicit criticisms of the Lee statue, reprinting Thomas Fortune’s New York Age opinion that said Lee was a “traitor” and “tried to perpetuate the system of slavery.”[8] Mitchell himself wrote that the dedication participants waved Confederate flags around and “No where in all this procession was there a United States flag. The emblem of the union had been left behind. The rebel yell, reinforced by a glorification of the lost cause was everywhere manifest.”[9] Both Fortune and Mitchell explicitly criticized the Lee monument dedication and the monument itself. Mitchell in particular suggested how un-patriotic these Confederate celebrations are, explicitly identifying it as part of the Lost Cause movement where people made myths out of war memory. Fortune and Mitchell expressed an explicit Black criticism of Confederate monument-building as a cultural reunion and an attempt to reassert Southern power on the national stage via the Lost Cause mythology.

Fig 2. Article by John Mitchell Jr. calling the Lee statue unveiling as a “glorification of the lost cause.”

Richmond planet. [volume] (Richmond, Va.), 10 May 1890. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84025841/1890-05-10/ed-1/seq-1/

[1] Richmond dispatch. [volume] (Richmond, Va.), 12 Oct. 1886. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85038614/1886-10-12/ed-1/seq-1/>.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Pierre Nora. “Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire” Representations, No. 26, Special Issue: Memory and Counter-Memory (Spring, 1989), pp. 7-24.

[4] Savage, 149.

[5] Richmond dispatch. [volume] (Richmond, Va.), 12 Oct. 1886. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85038614/1886-10-12/ed-1/seq-1/>.

[6] Cox, 62.

[7] Driggs, 32.; Howard, 96.

[8] Richmond planet. [volume] (Richmond, Va.), 07 June 1890. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84025841/1890-06-07/ed-1/seq-2/>

[9] Richmond planet. [volume] (Richmond, Va.), 10 May 1890. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84025841/1890-05-10/ed-1/seq-1/>