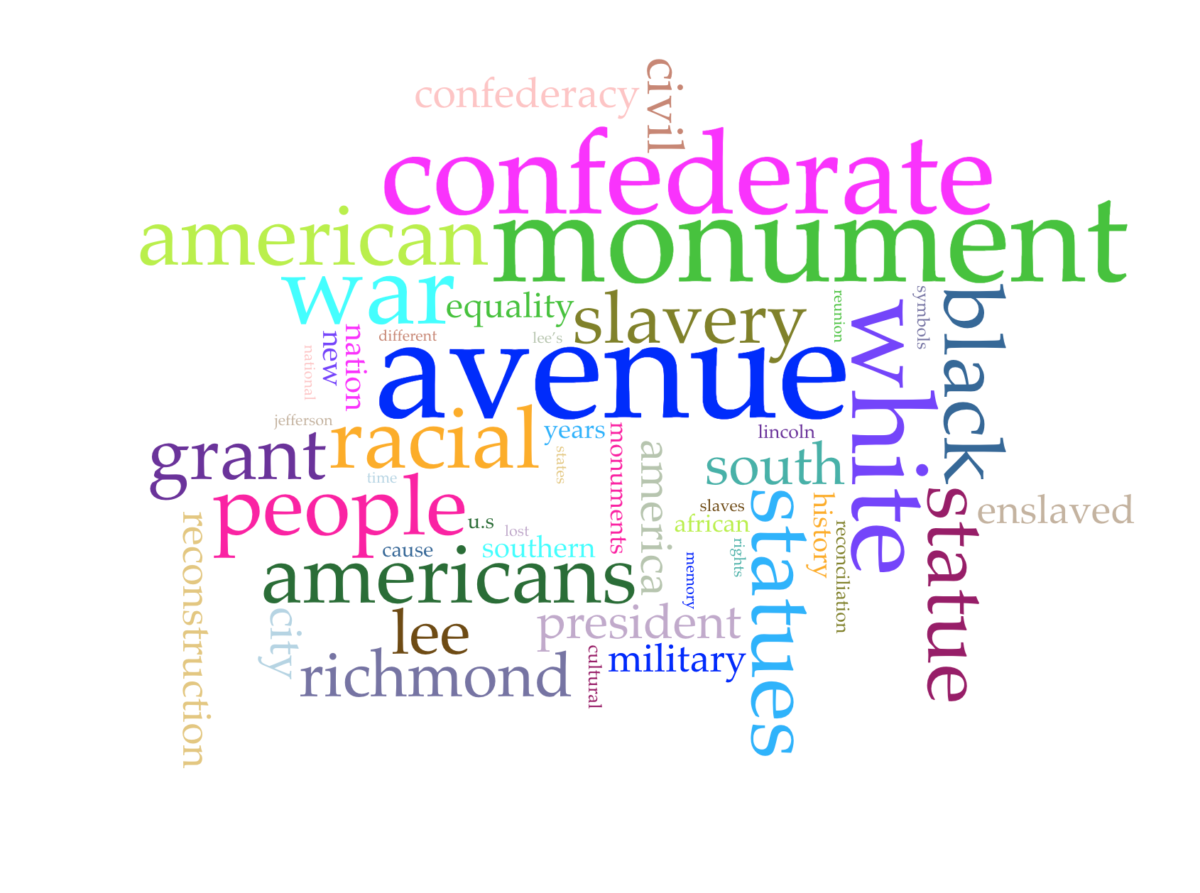

A digital public history website providing historical context about American race, memory, and the country’s different “heroes.”

During the summer of 2020 in the U.S., the world witnessed a racial reckoning: activists protesting the removal of Confederate monuments, the changing of schools and military base names that honor former enslavers, questioning the history of famous figures who had connections to slavery and white supremacy. Our project “Divided Union,” a website using ArcGIS and WordPress, responds to this reckoning by mapping Confederate statues’ effects on space and contextualizing the historical complexities of Ulysses Grant and Confederate names in military spaces. Together, we offer insight into the ways that digital methods and historical knowledge can contribute to current national and cultural debates around racial legacies and racial inequities.

Confederate Symbols in Military Space

A Short History of Confederate Base Names and The Move to Rename

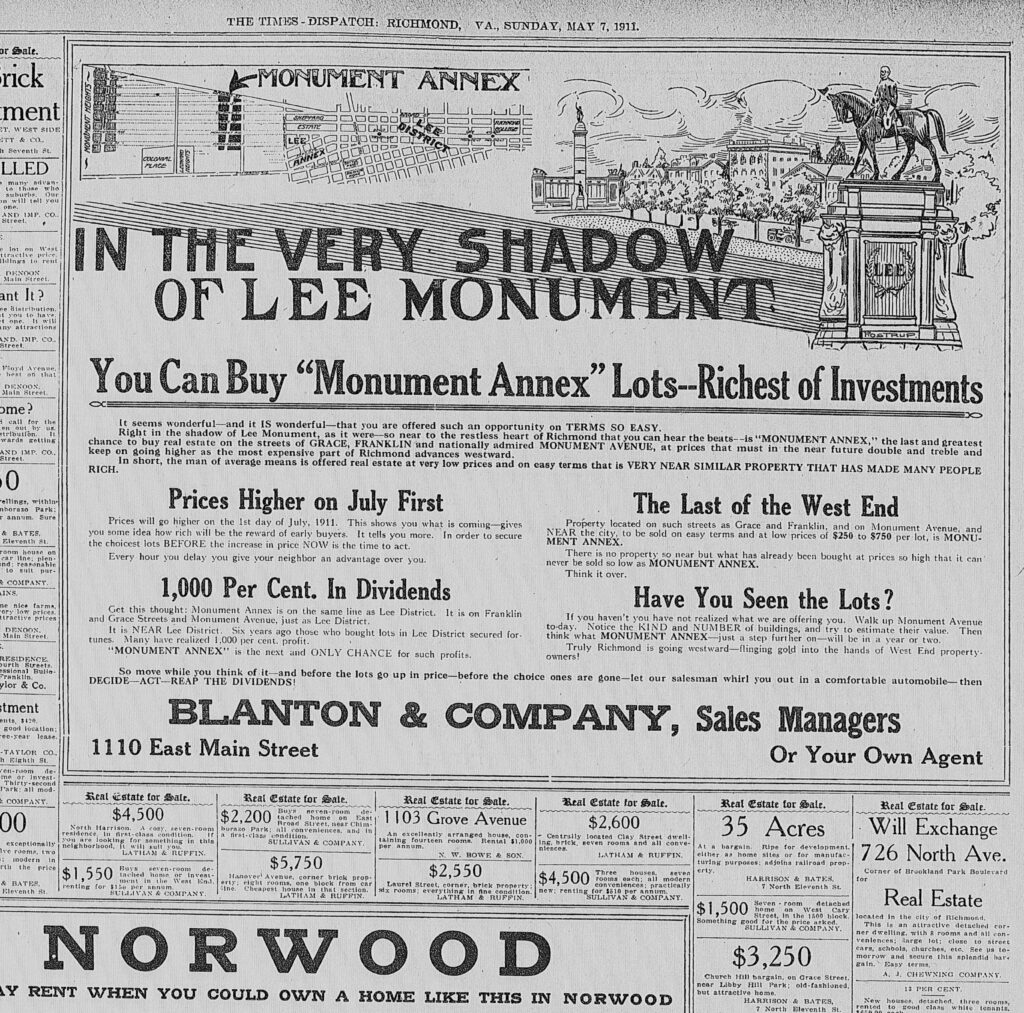

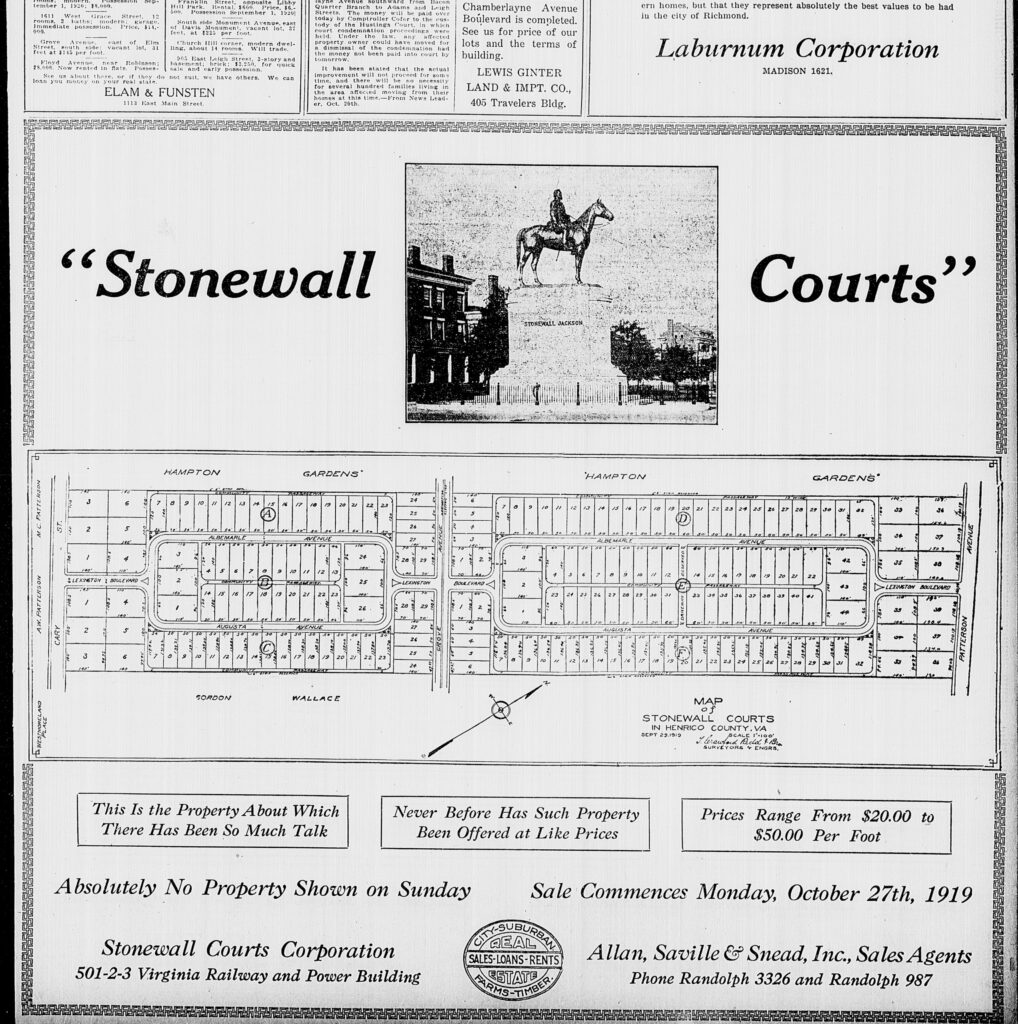

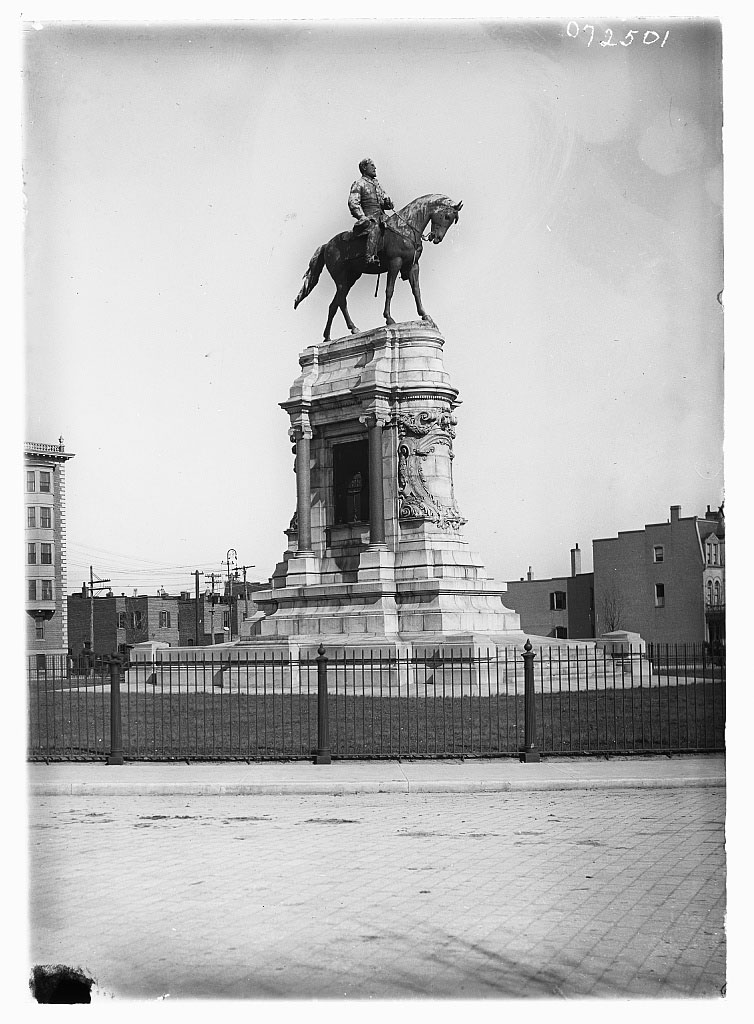

Statues and Residential Space

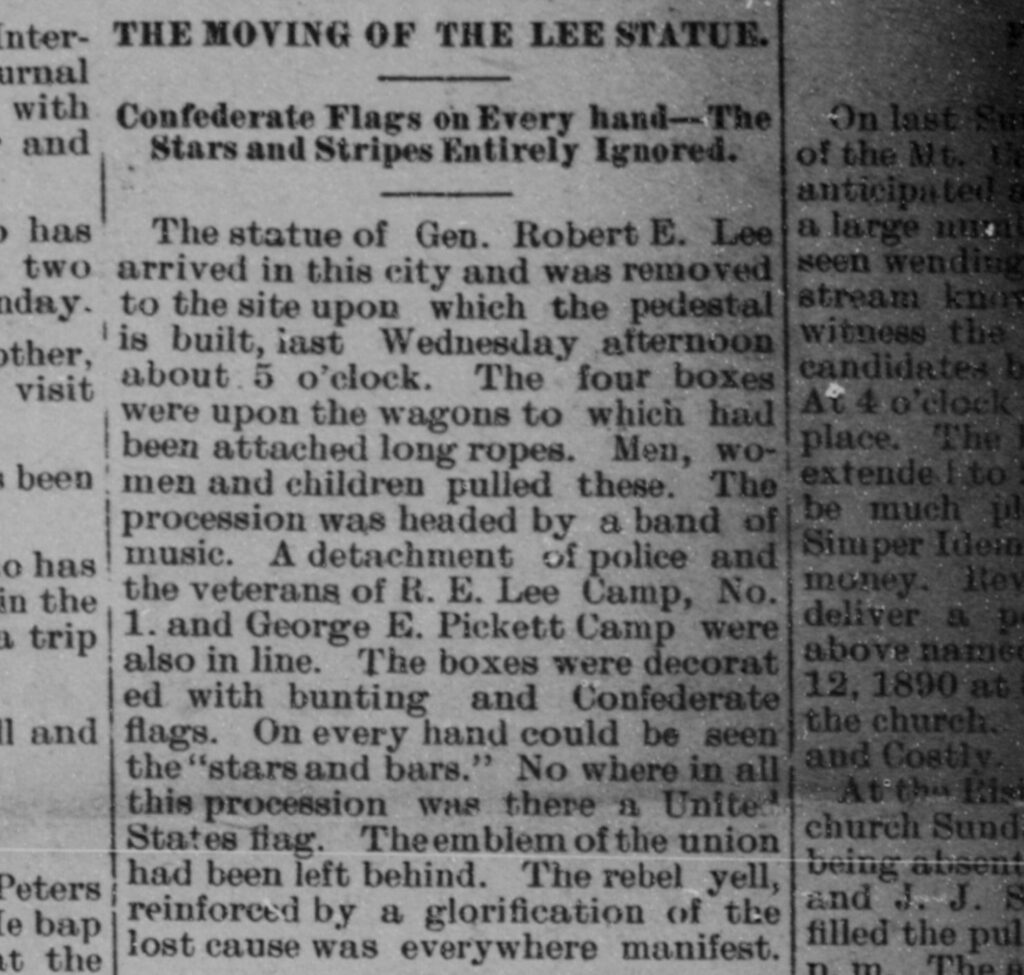

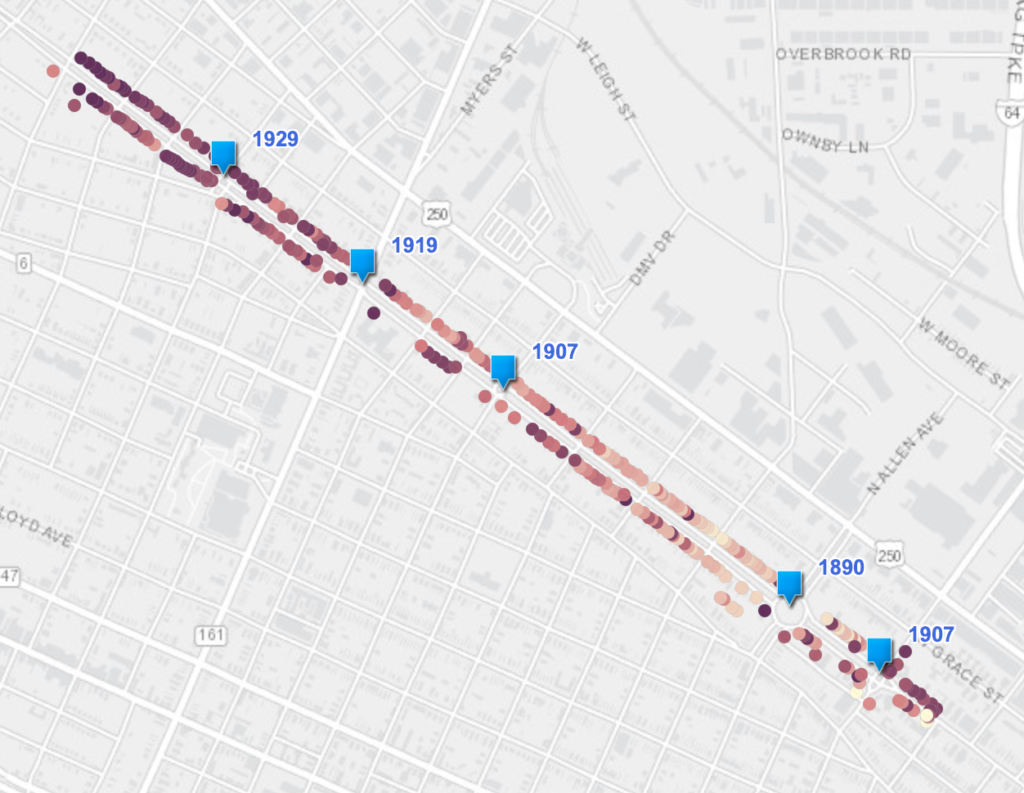

A Case History of Richmond’s Monument Avenue

This is a story about “…how the…drive for reunion both used and trumped race.”

David Blight, Race and Reunion (2001)

After the Civil War, which was fought between the Union in the North and the Confederates in the South, the U.S. had a lot of economic, cultural, and political problems. Racism and racial discrimination was still present, especially in the South. The federal government tried to help by deploying federal employees and passing legislation such as the Civil Rights Act of 1866 during a period called Reconstruction. But economic issues still persisted throughout the country and by 1876, when President Grant left office, federal intervention left the South, giving racial discrimination and violence free reign. David Blight’s book Race and Reunion (2001) explores the different ways that the drive for financial reunion and recovery between the North and South “trumped race,” or trumped the goal of racial reconciliation and reparation. Essentially, middle to upper class whites put their regional and political differences aside, in order for the country to get back on its feet economically.

Our project “Divided Union” explores two cases of the aftermath of the Civil War: a spatial history of Richmond’s Monument Avenue from 1880 to the 1930s and a brief history of Confederate symbols on U.S. military bases. Both of these exhibits detail post-Reconstruction era histories but also discuss statues and symbols that were recently questioned and protested in the summer of 2020. We hope our projects provide some historical context for anyone interested in the history of Confederate statues and symbols placed in residential areas and military bases.

Soldiers During World War II, June 1944. Source: Charles “Teenie” Harris © Carnegie Museum of Art, Charles “Teenie” Harris Archive. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/african-american-soldiers-served-during-world-war-ii-180974962/.