Richmond’s Monument Avenue: The Early Years

The first plat or map of Lee’s statue, drawn by city engineer C.P.E. Burgwyn in 1887, extended and renamed the western end of Franklin Street as “Monument Avenue,” demonstrating that Lee’s statue was always meant to be a part of a larger body of statues that honored the Confederacy.[1] Indeed, more statues were added on the avenue over time: both Jefferson Davis and J.E.B. Stuart in 1907, Stonewall Jackson in 1919, Matthew Fontaine Maury in 1929, and the sole non-Confederate and non-white figure, Arthur Ashe, in 1996. All of these statues, besides Ashe, were in the Confederate army and placed on the avenue within 22 years of Lee. Jefferson Davis was the President of the Confederacy and his statue in Richmond was one of the first projects of the United Daughters of the Confederacy. J.E.B. Stuart was a Confederate general known for his bold calvary tactics fighting under Lee.[2] Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson was one of Lee’s generals and became a Confederate legend of successful military strategy during the height of Lost Cause narratives in the early 1900s.[3] Matthew Fontaine Maury was a naval officer in the Confederacy and helped track different weather patterns in the U.S. Navy. Although Governor Lee and city engineer Burgwyn did not anticipate specifically who else would be honored on the avenue besides Lee, the erection of the other Confederate statues were very much planned.[4]

Burgwyn’s plat naming “Monument Avenue” also shows that the planned collection of Confederate statues were always intended to draw new residences and create a new subdivision outside of the city’s center. Indeed, more people built and resided on the avenue over time. The trend of residents moving out of the city center was already taking hold in other cities in the U.S. and around the world by the late nineteenth century due to urbanization, industrialization, and population increase. But Richmond was unique in that it used a number of statues honoring the Confederacy to entice white builders and residents to develop a new subdivision in the city. By the time the last Confederate statue was erected in 1929, Monument Avenue was already a success, with a total of 263 houses and apartment buildings lining the street embracing a unique patchwork of colonial architecture.[5]

As the monuments were added on the avenue further west away from the city’s center, over time, new houses and apartment buildings were also built westward along the monuments (see figure 3). Plots of land were sold westward by the three families who initially owned the tracts in the west end: the Allens, Branches, and Shepphards. The Allens, who owned the eastern part of the area, sold part of their land to the Lee Monument Association and later sold other plots of land to builders after the 1890 Lee statue unveiling.[6] In 1894, Otway Warwick, a partner in tobacco supplies firm of Warwick brothers, was the first to build a house on the avenue.[7] The J.E.B. Stuart and Jefferson Davis statue locations were announced in 1904, and the Branch family, who owned the next western tracts of the area, increasingly sold more plots of land after both the announcement in 1904 and unveiling in 1907.[8]

Monument Avenue Housing Map

Fig. 3. The chronology of homes and statues on Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia. The colored points show the year the homes were built; the darker purple, the later the year. The blue markers are the Confederate statues. Click each marker or point for more information about each specific statue or building. (Data provided by Sarah Shields Driggs, Richard Guy Wilson, and Robert P. Winthrop, Richmond’s Monument Avenue. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2001, in Richmond’s Monument Avenue, 247-254; “Whose Heritage? Public Symbols of the Confederacy” Southern Poverty Law Center.)

Both the Davis and the J.E.B. Stuart monument were strategically placed on the avenue in 1907 and drew residences and builders accordingly. The J.E.B. Stuart Monument Association had initially considered the Capitol square location downtown, as other Confederate monuments were there, but the city board of alderman offered $20,000 if they did not place it on the capitol’s grounds. Though they did not appropriate money explicitly for the Monument Avenue location, the city council’s discouragement away from the other obvious choice of the capitol and the reported amendment that “the site [will] be selected by the association and the City Council” is a clear indication that there were economic motivations for the Monument Avenue location.[9] The Davis statue was one of the main projects of the United Daughters of the Confederacy and they chose their location “follow[ing] the lead of the Stuart Monument Association.”[10] The site of Davis’ memorial was also where a Civil War fort had once stood and it provided an inner line of defense for the Confederate army.[11] Both Stuart and Davis’ statues are placed on each side of Lee, though Davis is a few blocks further west. The unveilings and festivities of both statues in 1907 saw reportedly record-breaking numbers of attendees and later an increase in the number of plots the Branch family sold.[12]

The growth of buildings on Monument Avenue reflect how the monuments themselves helped increase residential value. Out of the 303 buildings constructed on Monument Avenue from 1889 to 1964, the span from the years 1913 to 1928 saw the most growth. Within those fifteen years, 191 homes were built, comprising over 63% of the total buildings on Monument Avenue, with 27 homes built in just the year 1926.[13] (see figure 3). Part of this reflected other national trends of real estate construction throughout the U.S. at the time, but part of this was also because by 1913, Monument Avenue had already been established as a grand boulevard that was desirable to live on. Ellen Glasgow’s book Life and Gabriella published in 1916, describes a scene where a character takes others for a drive on Monument Avenue, excitedly exclaiming “Here are the monuments!…you don’t see many streets finer than this in New York, do you?”[14] By 1913, there were already 89 houses built on the avenue, comprising 29% of the boulevard, so a number of grand houses with colonial architecture were already built and the boulevard itself was starting to reap the rewards from city planners constructing sidewalks and planting trees in 1904.[15] Although Glasgow’s character is fictional, their exclamation reflects how the monuments were used as a signifier for the avenue, which displayed the success, wealth, and progress of Richmond similar to other “fine” and desirable streets in New York. Though this is only a novel and not the personal testament of a resident, the fact that Glasgow, who was a resident of Richmond, wrote about a character’s excitement over the monuments shows that the monuments themselves were the centerpieces to the resident’s ideas and perceptions of the avenue.

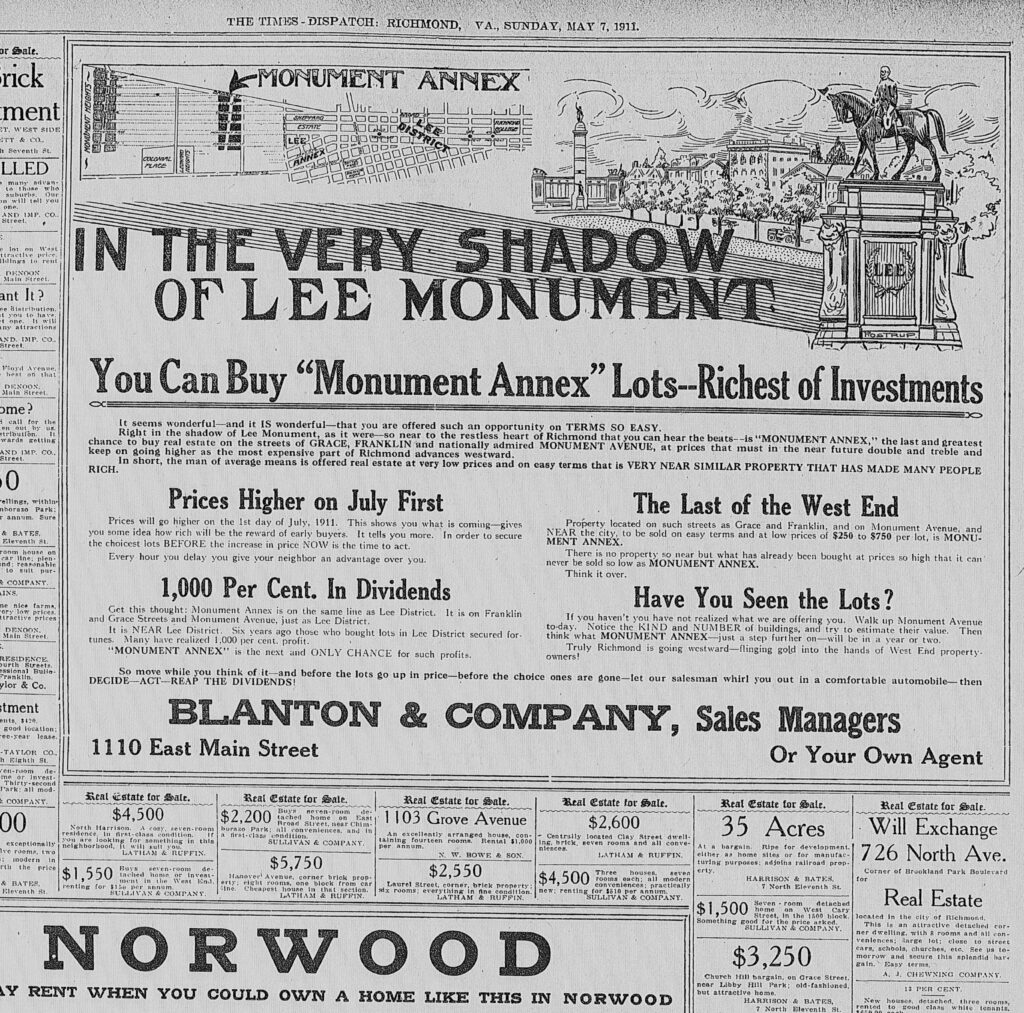

Newspaper advertisements for building and buying houses on and nearby Monument Avenue also reveal that the monuments helped drive real estate. In 1911, an advertisement titled “In the very shadow of Lee Monument” encourages buying lots on Monument Avenue as an investment, as “Richmond is going westward – flinging gold into the hands of West End property-owners!”[16] Here, Lee’s shadow and the implied other statues added westward are used as an incentive to draw buyers and investors. Similarly, two weeks after the Stonewall Jackson monument was unveiled in October of 1918, an advertisement “Stonewall Courts” appeared with a drawing of the Jackson statue alongside a map of Stonewall Courts property with accompanying text such as “This Is the Property About Which There Has Been So Much Talk” and “Never Before Has Property Been Offered at Like Prices.”[17] Though these properties were about a mile off of Monument Avenue and a few miles from the Stonewall Jackson monument, this advertisement captures the power Monument Avenue’s statues had over Richmond’s real estate in the western area of the city. These are examples of real estate companies using the avenue to create new residential areas based on the statues. These advertisements, amongst many others, demonstrate that statues can drive residential and cultural value beyond the spaces they inhabit.

The times dispatch. [volume] (Richmond, Va.), 07 May 1911. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85038615/1911-05-07/ed-1/seq-28/>

The people who bought, developed, and lived in the buildings on Monument Avenue in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were mostly white members of Richmond’s elite business class, with the exceptions of some white middle class people who rented apartments beginning in the 1910s. A significant amount of partners and presidents of a variety of profitable companies lived on Monument Avenue, including people like James F. Walsh, superintendent of Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad Company, Langhorne Putney of Stephen Putney Shoe Company, and Leon Strause of the leaf tobacco trade and President of Chelf Chemic Company.[18] Some architects who helped build houses on Monument Avenue also lived on the avenue themselves, such as Carl Lindner and Max E. Ruerhrmund, two architects who designed a number of houses on the avenue in the 1920s.[19] Sarah Driggs says on Monument Avenue, “builders, architects, and patrons could play the great American game of proving you have arrived by building a large house at a prestigious address.”[20] Due to city and real estate investment in the statues, Monument Avenue became the place where Richmond’s white business class wanted to invest in and build on. Due to the cultural and economic investments in the statues and Richmond’s real estate market, it is no surprise that the people who built and lived on the avenue were mostly business elites and people who had the means to display their wealth.

Monument Avenue was a specific, tangible place to rebuild Richmond economically by creating a desirable new subdivision and indirectly drawing Northerner investment and involvement in a European-style boulevard. Monument Avenue projects the desire of showcasing the progress of Richmond by imitating the classic Greco-European layout of the famous and romanticized boulevard. Reiko Hillyer argues Monument Avenue shows that Richmond “wanted to associate [the] boulevard with [the] modernization of the city” and demonstrates the integration of the Lost Cause with the new South, and Confederate memorialization with urban progress.[21] The concept of a grand avenue consisting of a row of trees lining a wide street is specifically associated with European cities such as Vienna’s Ringstrasse road, which Adolf Hitler was reportedly a significant admirer of. Vienna’s boulevard as well as Paris’ were city planning inspirations to American cities such as New York’s Fifth Avenue and Cleveland’s Euclid Avenue.[22] So, in one way, the statues and the avenue fits into the greater historical period of the American Renaissance, trying to encourage civic improvement and engagement that reflects European styles, successful city planning, and modern progress.

Historic American Buildings Survey, Creator. Block Monument Avenue, Richmond, Independent City, VA

. Richmond Virginia Independent City, 1933. translateds by Schwanmitter, and Price, Virginia Bmitter Documentation Compiled After. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/va1630/.

In another way, Monument Avenue reveals an American North acquiescing to honor the Confederacy through not only Northern investment but also by Northern participation; by helping build the avenue, Northerners compromised racial integrity for economic profit. Some of the sculptors, architects, and planners for the monuments themselves and the avenue were from the American North and even from the American West and Europe.[23] Evie Terrono discusses some of the Northerner architects and sculptors of the statues, claiming they might not have identified with Lost Cause ideologies but helped construct them through building the avenue because “they recognized the potential [to showcase their skills] …of defining this remarkable residential enclave.”[24] By buying into Monument Avenue and its symbolism of both Confederacy celebration and European modernism, Northerners once again ignored the racial implications of this work and chose to center financial and political reunion instead.

Many white residents and Richmonders saw Monument Avenue as a beautiful avenue that was a site to showcase social elitism which also reflected Richmond’s and the South’s cultural comeback post-Reconstruction on the national stage. Ellen Glasgow’s character in the Life and Gabriella compares the avenue to New York City’s extravagance and also to the progress of Denver, saying “it shows what the South can do when it tries.”[25] A real estate newspaper advertisement stated in 1911 that Monument Avenue was “nationally admired.”[26] These representations indicate that residents and citizens of Richmond realized the national implications of Monument Avenue in that it represented a successful South post-Reconstruction. Indeed, through Monument Avenue, many Richmond citizens saw a financial and cultural comeback of not only Richmond but also the South more generally in a post-Reconstruction world.

[1] Driggs, 100.

[2] Ibid, 56.

[3] Ibid, 74.

[4] It should be noted that these five men were not only involved in the Confederacy. Lee, Davis, Stuart, and Jackson served in the U.S. army before the Civil War and many fought in the Mexican-American War in the 1840s. As noted, Maury was in the U.S. Navy before the Civil War.

[5] Driggs, “Appendix: The Buildings of Monument Avenue,” in Richmond’s Monument Avenue, 247-254.

[6] Ibid, 101.

[7] Ibid, 99.

[8] Ibid, 103.

[9] The times dispatch. [volume] (Richmond, Va.), 11 May 1904. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85038615/1904-05-11/ed-1/seq-7/>.

[10] Driggs, 67.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Cox, 62; Driggs, 103.

[13] Driggs, “Appendix: The Buildings of Monument Avenue,” in Richmond’s Monument Avenue, 247-254.

[14] Glasgow, 506.

[15] Driggs, 101.

[16] The times dispatch. [volume] (Richmond, Va.), 07 May 1911. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85038615/1911-05-07/ed-1/seq-28/>

[17] Richmond times-dispatch. [volume] (Richmond, Va.), 26 Oct. 1919. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045389/1919-10-26/ed-1/seq-51/>

[18] Driggs, 113-116.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid, 97.

[21] Hillyer, 132.

[22] Alan Ehrenhalt. The Great Inversion And the Future of the American City. New York, NY: Random House Inc., 2012, 24-32.; Evie Torrono. “Of Triumphal Arches and Vestal Virgins: Classical Ideals and Urban Uplift on Monumnet Avenue,” On Monument Avenue. January 12, 2018. https://onmonumentave.com/blog/2018/1/12/of-triumphal-arches-and-vestal-virgins-classical-ideals-and-urban-uplift-on-monument-avenue-1#_ftn1=.

[23] Hillyer; Savage; Torrono.

[24] Torrono.

[25] Glasgow, 496, 7.

[26] The times dispatch. [volume] (Richmond, Va.), 07 May 1911. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85038615/1911-05-07/ed-1/seq-28/>